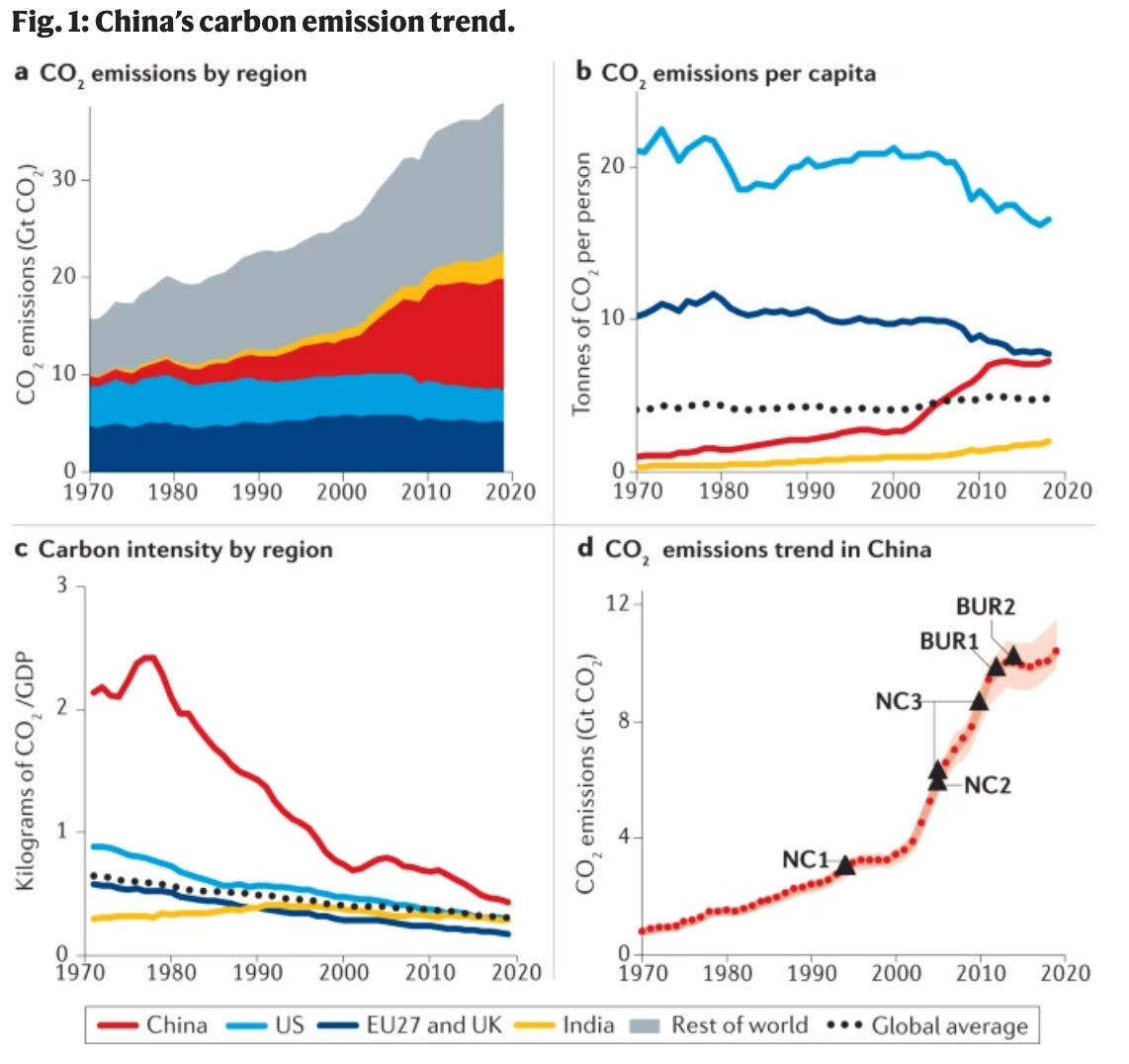

The trajectory of Chinese emissions is probably the single biggest determinant of the success or failure of global climate action. Is China the Climate Boogeyman or Hero of the Clean Energy Revolution? It is the world’s largest emitter at 28% of the total (although about half per capita as the US), which is little wonder when one considers that over the last 30 years GDP per capita has grown x30, whilst the urban population has grown by the equivalent of all of the EU plus Japan. China is by far the biggest consumer of coal globally (53%) and accounts for half of the global pipeline of planned plants (Carbon Brief have a fantastic map showing all plants at different points of the cycle), and more than half of global steel and cement production. As well as being a huge domestic consumer, China until recently was the major financier of new coal plants overseas (although overseas projects are dwarfed by domestic coal consumption). Chinese demand is also a large factor in deforestation as it is by far the biggest market for beef and soy from Brazil, representing about half of all beef exports and nearly 80% of soy exports. On the other hand, China is expected to account for 45% of global renewable additions over the next 5 years, it produces 80% of the world’s solar panels, 77% of the world’s lithium-ion batteries, and plans to build 150 new nuclear plants in the next 15 years.

Given China’s critical role in determining our shared climate fate, I wanted to spend more time understanding the evolution of and possible trajectory of its emissions. I’m breaking this topic into two parts to make it more digestible, today looking at the current state of affairs and next week examining the roadmap to 2060.

Paper: Challenges and Opportunities for carbon neutrality in China (Tsinghua University)

Key targets now are peak emissions by 2030, carbon neutrality by 2060 [note that it is carbon neutrality, not GHG neutrality, so doesn’t include methane, nitrous oxide, etc, which are conspicuously absent from China’s mid-century roadmap, although they recently committed to tackle methane in the US-China climate declaration at Glasgow]

China has made significant progress in reducing the carbon intensity of its economy, with a 48% reductions in emissions per unit of GDP between 2005 and 2020, with a target of >65% reduction over 2005 levels by 2030

History of decarbonisation targets, which each region is responsible for meeting:

12th Five Year Plan (2011-2015) saw thousands of inefficient power plants and factories closed, resulting in cumulative emission reductions of 1.5GT

13th FYP (2016-2020) targeted cutting energy and carbon intensity by 15% and 18% respectively, achieved by increasing % of non-fossil energy and having emission standards for coal plants

14th FYP (2021-2025) targets cut of energy and carbon intensity by 13.5% and 18% respectively

2030 NDC - targets 65% reduction of carbon intensity and 25% of energy mix as non-fossil (revised up from 20%)

Carbon intensity is particularly high in some underdeveloped central and western regions that have a lot of industrial activity and fossil resources that get exported to more developed coastal regions in the form of finished products and power.

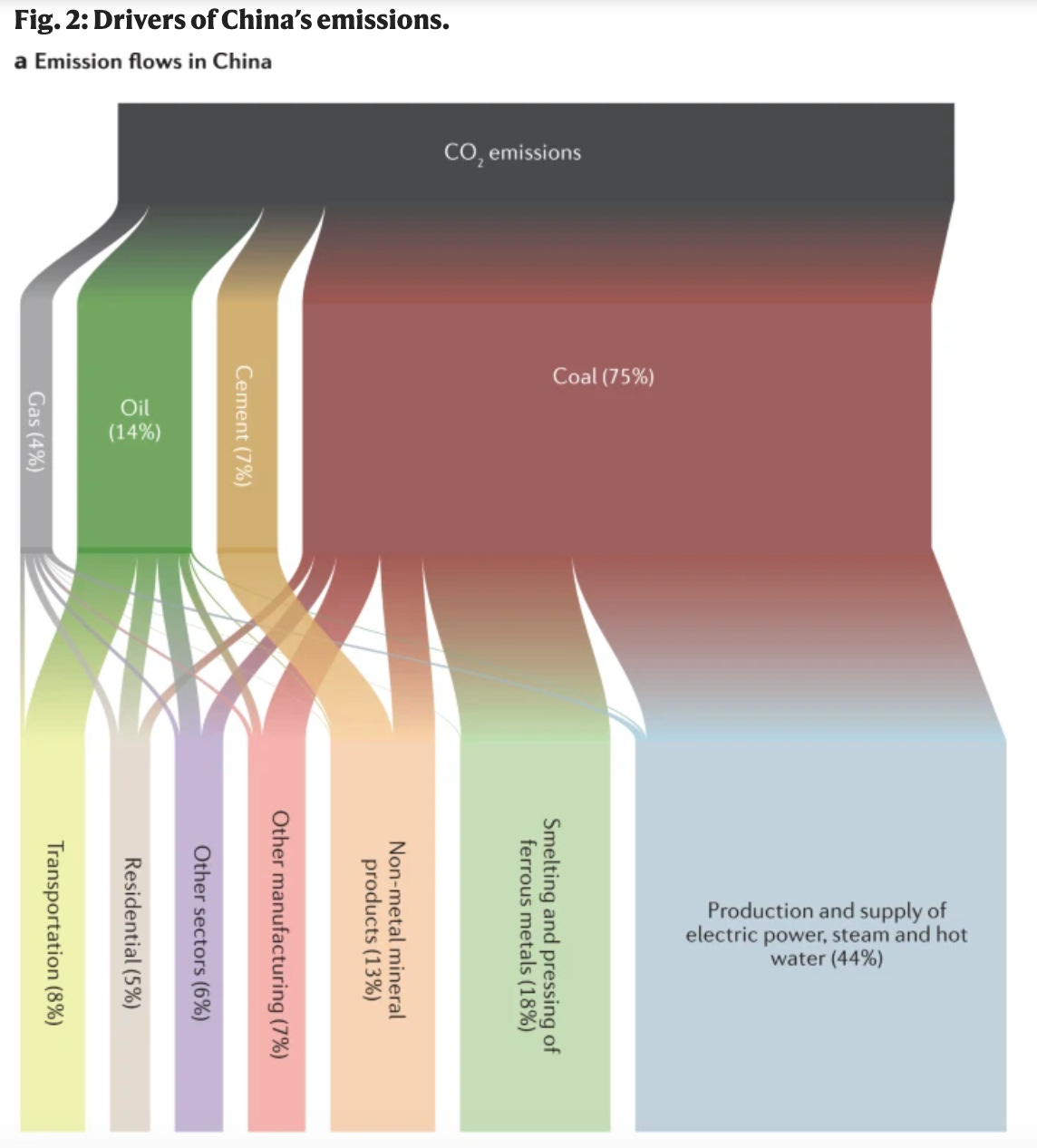

Coal use accounts for 75% of China’s emissions in terms of primary emissions. 44% is power production with coal, and 38% is from manufacturing with steel (18%) and cement (7%) as the biggest components

Main challenge in reducing emissions is therefore in phasing out, or “down”, coal. There are some policies around air quality and reducing overcapacity of coal plants that suggest that coal-related emissions might peak by 2027, but challenges remain - a lot of the coal plants were built recently so have long remaining life times and as part of the COVID stimulus a lot of new coal projects were green-lit.

China’s trade-related emissions rose sharply between joining the WTO in 2001 and peaked in 2008. Shifting dynamics of trade now see them importing more raw materials and labour-intensive products from lower-income developing countries and exporting more machines and finished goods.

China is now moving from more investment-driven emissions (i.e. infrastructure) to consumption-driven.