I recently had the privilege of presenting to a large family office on the role innovation has to play in carving a path to Net Zero. Whilst there is a lot of ink spilt around specific decarbonisation innovations, it struck me that there was far less discussion on the general framework for innovation and how it evolves. Also, when we zoom out and look at the ongoing process of innovation and our collective direction of travel, it leaves more room for optimism than a mere snapshot does. A big part of what we’re doing at Keeling Capital is equipping people with the tools they need to make better assessments and decisions around the climate transition - frameworks, not just information. In that vein, I’m here publishing the core elements of this presentation. Whilst this narrative is generally one of climate optimism, let me state clearly that optimism isn’t the same as complacency. We are already baked into some materially adverse consequences from climate change, and there are other areas around environmental sustainability that are serious cause for concern, such as ocean health and biodiversity loss. However, by widening the aperture and timeframes, we have evidence that we can stave off calamity, mostly thanks to the transformative impacts of innovation.

Along current trajectories…

How many news articles have you seen that contain those words, followed by some dire, seemingly inevitable consequences? If you do a Google search of “along current trajectories will run out of”, you will get a pretty strong sense that it is all over for humanity. We might as well just trundle off to our dying hole and wait for it to be over.

Of course, the end has always been nigh. Famously, or infamously, Thomas Malthus predicted at the end of the 18th century that the world would soon breach its carrying capacity, guaranteeing mass starvation. Since then, as we all know, the world population has gone from something like 800 million to over 7 billion. What has consistently intervened to stave off malthusian collapse? Innovation and technology. The Malthusian Fallacy refers to forecasts of doom that are predicated on one change without taking other changes into account. Another way of saying it is that “current trajectories” don’t stay “current” for long.

I recently cross-posted a piece from Roger Pilke that made this point brilliantly. From John Kerry’s New York Climate Week speech this year:

“We're currently heading towards something like 2.4 degrees, 2.5 degrees of warming on the planet”

Compare that with another speech from exactly two years previously:

“Currently, as we’re talking today, we are regrettably on course to hit somewhere between 3, 4 degrees at the current rate.”

To be clear, something like 2.5 degrees of warming is a disastrous outcome, but, in a challenge where we are measuring success in 0.1 degree increments, a shift in expectations from 3-4 degrees to 2.5 degrees in two years is astonishing. To get a real sense of trajectories, we need to look not just at the first derivative - the rate of change - but also the second derivative - the rate of change of the rate of change.

Getting exponential

How can “current trajectories” be shifting so rapidly? Unsurprisingly, the answer lies in the exponential scaling of low-carbon technologies and the possible futures this opens up. For this section, I’m indebted to the work done by RMI in this report and summarised in this excellent blog post.

The world is on a tear with renewables deployment and solar in particular. Staggeringly, China solar installations this year stand at 210GW - that is almost double the total installed solar capacity of the US (i.e. cumulative total installations across history) and four times the amount China installed three years ago. Wild!

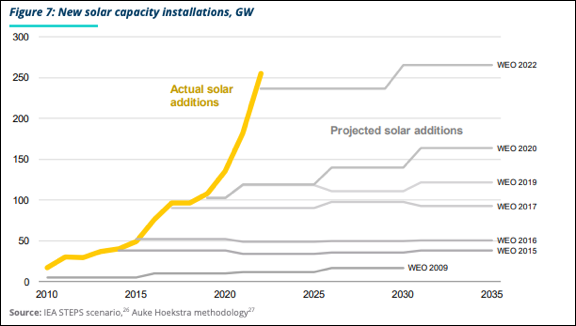

But, whilst the exponential path of renewables is encouraging, what is even more encouraging, is that forecasters have been consistently too pessimistic about future prospects. That is true for even the most bullish prognostications, but we’ll just pick on the International Energy Agency, since they are the de facto global source for information on the energy system.

The above chart shows in the grey lines the forecasts in the IEA’s World Energy Outlook. It is almost comical how fast they become obsolete and how reliably they fall woefully short of reality. Also, if those installation numbers for China are confirmed….

Why are bottom-up forecasts consistently too pessimistic? It is because the challenges are obvious to everyone, but the solutions are not. However, because the challenges are obvious to everyone, you can guarantee that there are some smart people out there working on solutions. We can’t begin to imagine the bounty of our collective imagination. Or, citing Orgel’s second rule:

Evolution is cleverer than you are.

A framework of innovation: Technological Revolutions

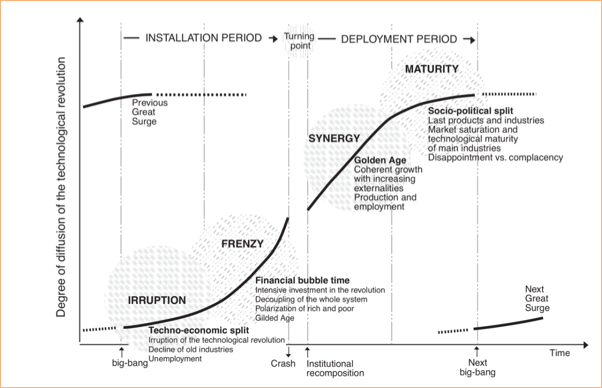

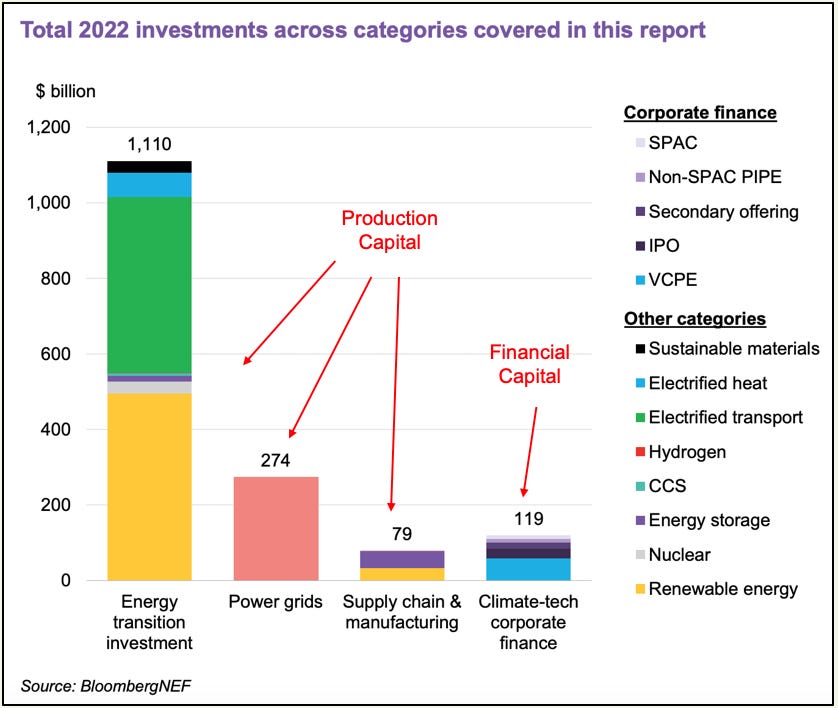

Innovation is all very well and good, but for solutions to make a difference on a planetary level, they need absolutely massive scale. How do they move out of the venture bucket, and into the infrastructure / corporate adoption bucket? To explain this, we’ll borrow from the work of Carolta Perez and her excellent (and very readable) Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital. Technologies go through a repeated development cycle. In early development they suck in speculative financial capital, which generally gets overdone as the promise becomes clear but the technology hasn’t reached maturity. There is normally some kind of reset that washes out the hype, and then over the coming decades the technologies get integrated into industry and corporate balance sheets (or “production capital”) takes over the real scaling. I think we can say that Cleantech 1.0 and renewables bears some signs of that, where a lot (or, what seemed a lot at the time) of venture money went into things like competing technologies to solar PV. They got washed out in the wake of the financial crisis, but now deployment has reached a level where we’re starting to hit the meaty bit of the S-curve. Venture -> Infrastructure leap achieved.

You can see from BNEF’s energy transition investment report from last year, that the financial capital bucket, which includes VC, SPACs (RIP) and the like, is dwarfed by the production capital dollars.

Probably the best example of a relatively small amount of venture dollars, or “financial capital”, translating into a shift of massive amounts of production capital. Consider this: Tesla raised $60mm of venture capital before going public. Today, in the US alone, there have been more than $170bn of investments (completed or announced) in battery and EV manufacturing facilities. About $500bn (the green half of the big bar above) was invested across electrified transport infrastructure globally in 2022 (it doesn’t include the value of EVs sold).

Could other low-carbon technologies follow the path of EVs?

Sometimes we hear it bemoaned that too many of the climate venture dollars go into the “wrong places” - i.e. they aren’t allocated to sectors proportionally to share of emissions. We think this is stupid. There is nothing special about “climate dollars”; they are totally fungible with “non-climate dollars”. If EVs have been significantly over represented in climate tech VC relative to share of emissions, it is because the commercial opportunity ripened first. But now the early innovation dollars are finally starting to shift with other heavy emitting sectors receiving proportionally more of the climate VC investment, particularly in the regions driving the breakthrough innovation - North America and Europe. (China climate tech in particular is still dominated by mobility investments.) This gives us an indication that innovation and the corresponding commercial opportunity is picking up in other heavy emitting sectors, no doubt catalysed by the near bottomless appetite for low carbon solutions to reach corporate and national Net Zero targets.

Where are the innovation opportunities from here?

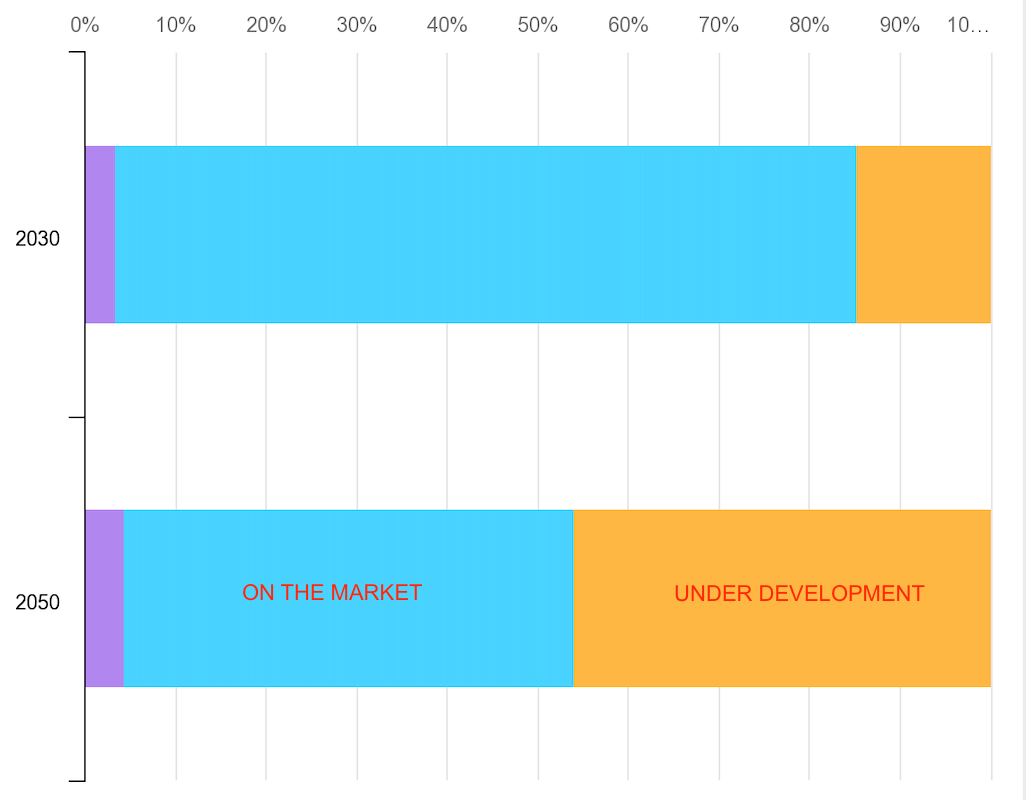

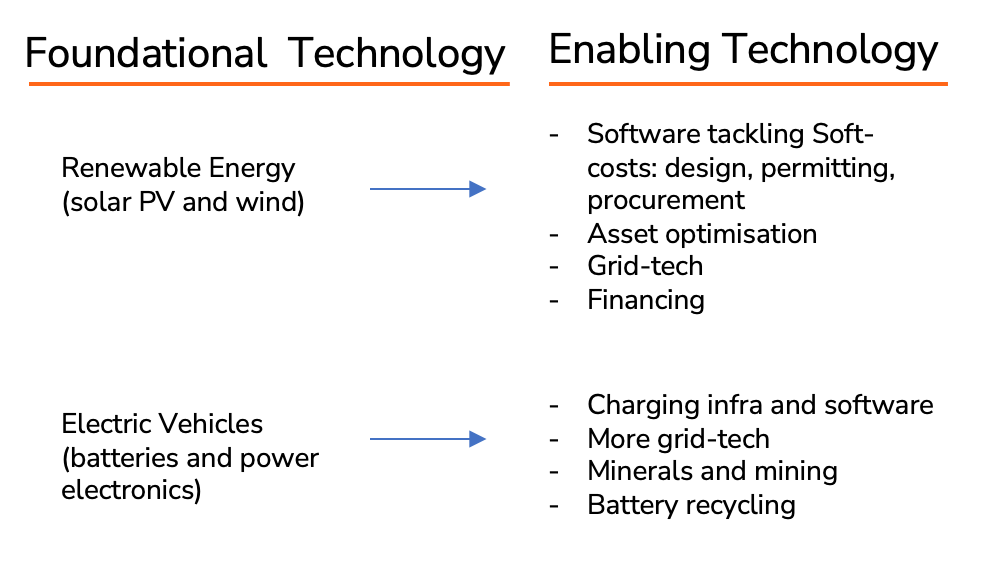

We tend to think of innovation opportunities for climate transition as falling into two groups- Foundational Technologies and Enabling Technologies. We need both. If you look back to the IEA’s roadmap to Net Zero, they suggest that approximately half of the emissions reduction for Net Zero 2050 will be scaling existing stuff (solar, wind, batteries, EVs, heatpumps) and half will be stuff that isn’t yet mature (carbon capture / removal, green molecules, advanced nuclear, geothermal). Note that they put less than 5% of the transition into the “behaviour change bucket.

Both of these buckets require many, many new innovations to bring them to climate relevant scale. The foundational technologies are perhaps more obvious, given that they are freshly commercialising new engineering breakthroughs. But as these foundational technologies scale, it opens up new opportunities for profitable innovation. As these become sizeable industries in their own right, it offers new markets to serve. Also, as bottlenecks to scale appear, they become obvious opportunities for value creation, which innovators apply themselves to unlocking.

Progress is set to accelerate

The progress made to date in decarbonising has been insufficient, but not negligible. What progress has been made has been made by a teeny tiny number of people, working in the face of indifference at best and hostility at worst. We owe them a huge debt of gratitude. 🙏

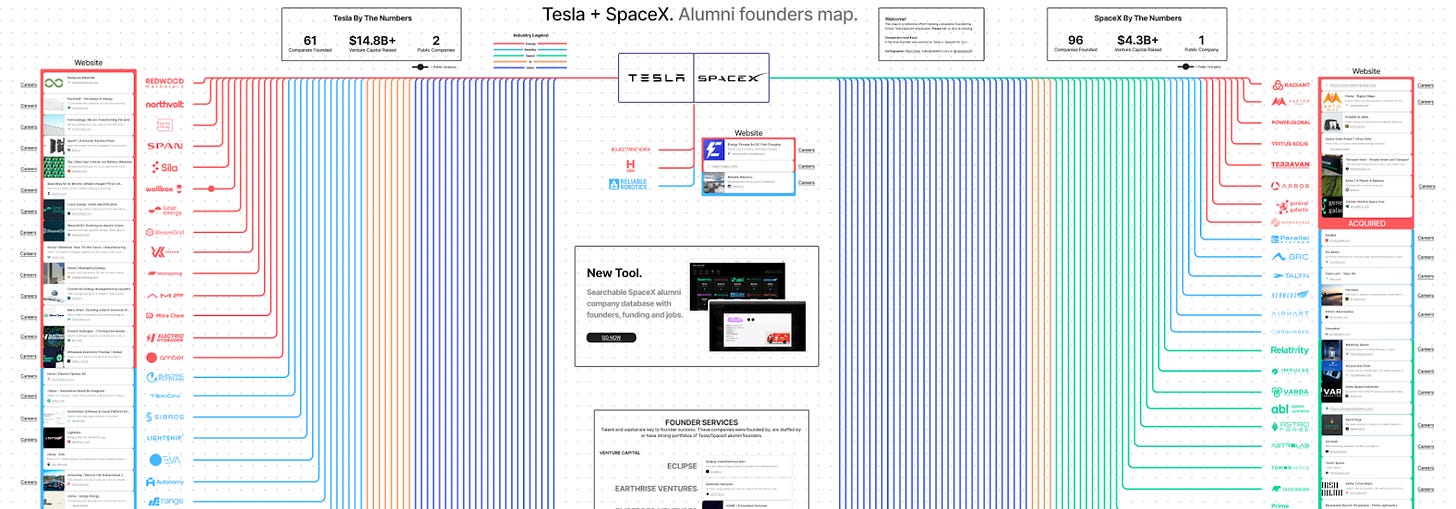

That situation has shifted radically over the last couple of years. Firstly, policy makers across multiple regions have been much more aggressive in pursuing decarbonisation policies, most notably the US with the Inflation Reduction Act, which raised policy ambition globally. Secondly, the formation of human capital in this space is astonishing. That includes people like Mike Schroepfer (former CTO of Meta) dedicating themselves entirely to the climate fight and organisations like Terra.do, Climate Draft and Work on Climate focussed on getting people into the climate space from other industries. Also, much less appreciated, there is now for the first time a cohort of people who have been involved in scaling climate hardware companies. Nothing demonstrates this more powerfully than the huge ecosystem of companies that have been started by Tesla and SpaceX. Alumni of those two companies have gone on to found over 150 companies and raised almost $20bn of venture capital. Not all of that capital is in climate, but most of it is. And that only speaks to the founders, to say nothing of the technically brilliant people who have gone to work for other companies.

So, sure, we haven’t made enough progress yet, but we’re only just starting to try!

Don’t worry. Be Happy.

It is easy to slip into a dark place when one falls down the “along current trajectories” rabbit hole of doom. And, indeed, we’ve done a lot to screw up the planet and there is much to be saddened by. However, there are a few reasons why we should let this get us down.

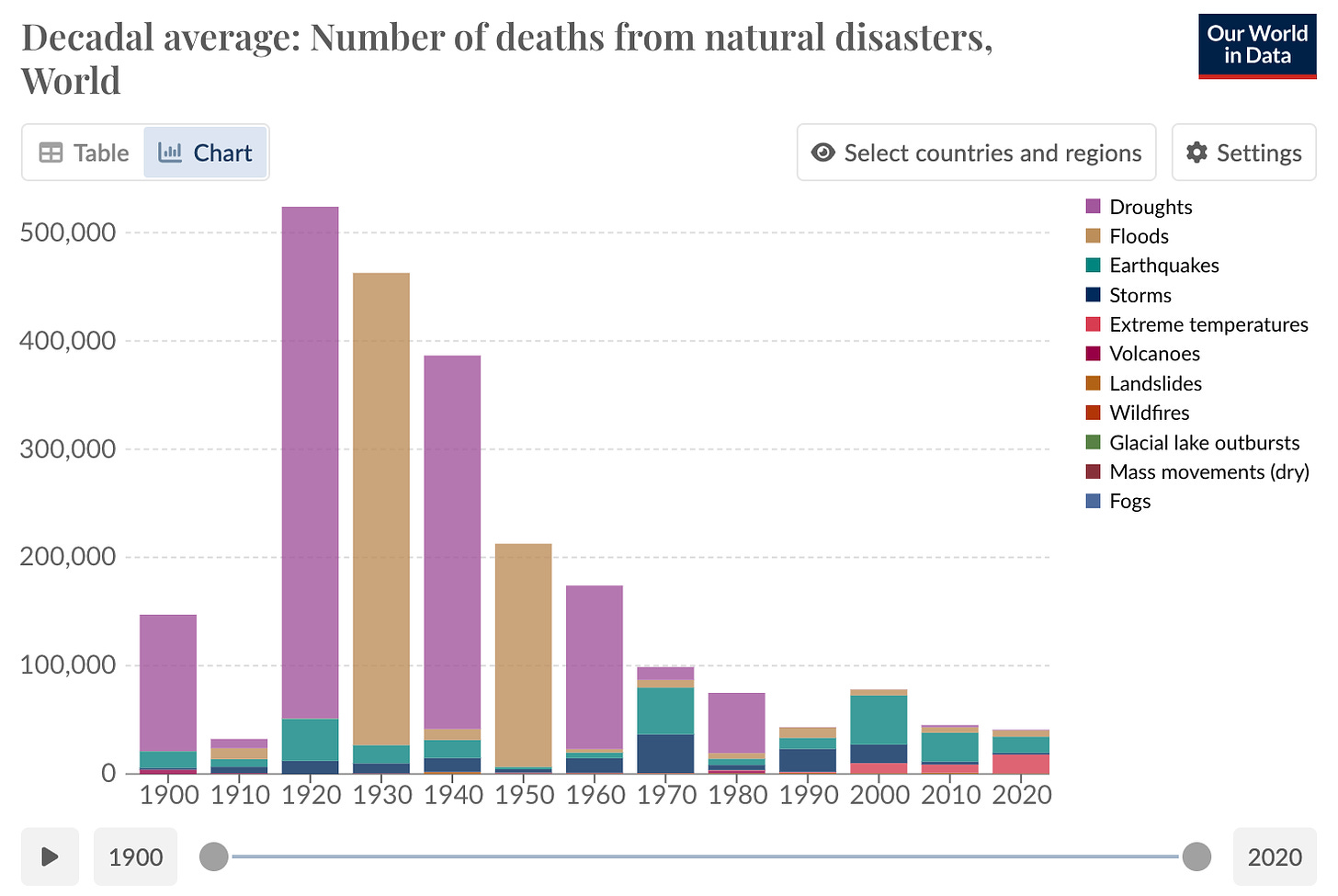

Climate change is not the only thing going on. Whilst the climate and other planetary boundaries are moving in the wrong direction, this is not the only thing happening in the world. We continue to lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty year over year, materially improving their well-being across any metric we might care to pick. You may be surprised to learn that deaths from climate-related events have fallen precipitously over the last century. Specifically, there has been drastic reduction in loss of life from floods and droughts over the 20th century.

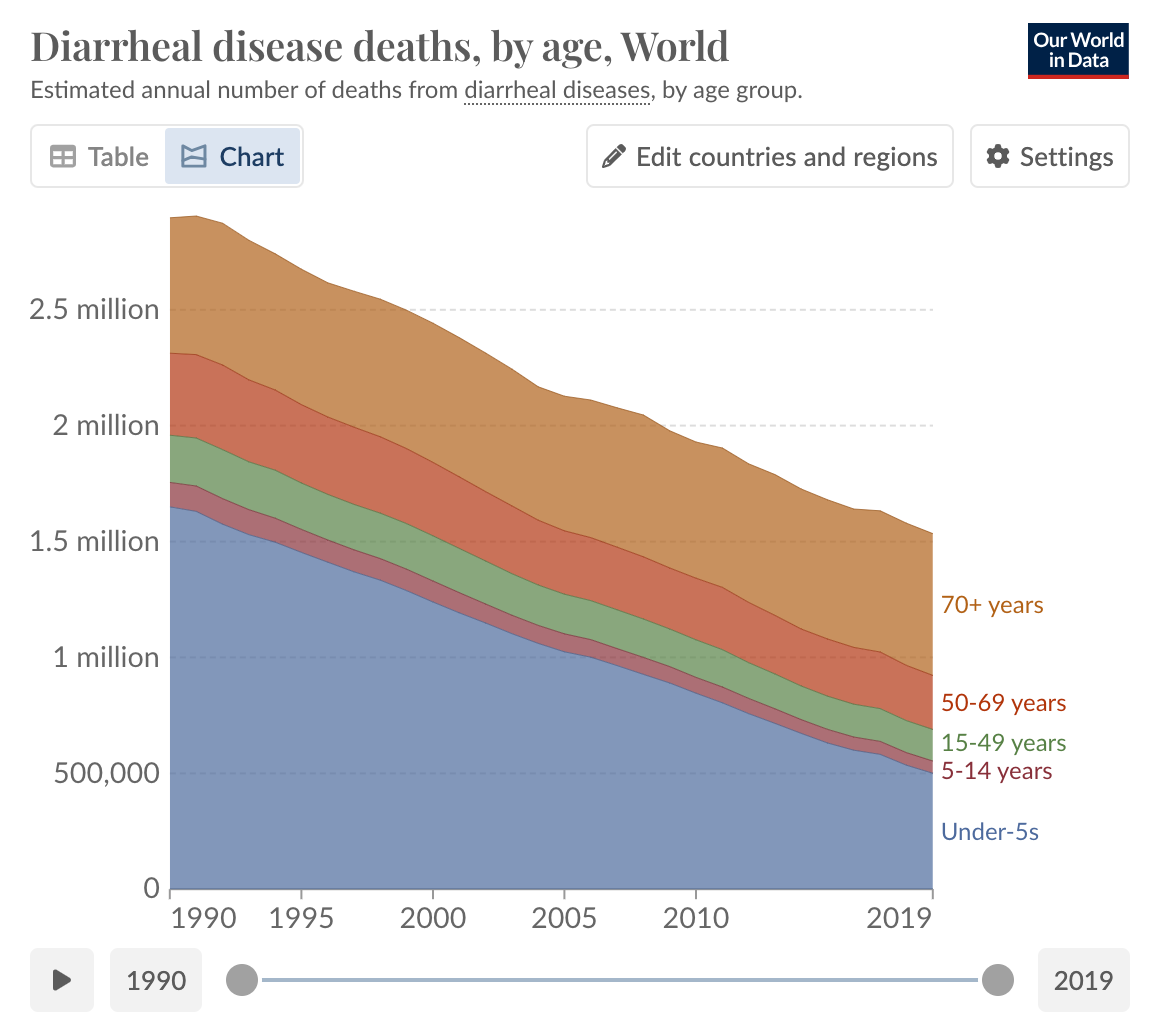

Now, you may notice that deaths from extreme temperatures have been ticking up from a low base in recent years (the small red bar above), 17k average per year more recently. And you would have to say that this number is going to go up; the impacts of climate change are non-linear. The World Health Organisation estimates that climate change may result in 250,000 deaths per year between 2030 and 2050. That would obviously be a very sharp reversal of the long-term trend of greater resilience to climate events, but let’s pessimistically say it gets realised. That number - 250,000 people - seems like a lot. But relative to what? Almost 7 million people a year currently die from air pollution (4.2 million from outdoor air pollution and 2.5mm from indoor) - a number that is very likely to drop with reduction of coal, a switch to EVs and improved access to clean cooking. Today, tragically, half a million children under the age of 5 die of diarrheal diseases every year. But the other half of that story, which gets zero coverage, is that a million less children die annually from diarrheal disease today than they did just 30 years ago, even as the world has added a couple of billion people (all of them passing through the 0-5 age group, in the traditional manner). For now, climate is not the only, or even the most important, vector for human well-being.

Climate anxiety isn’t accretive to climate transition. Nurturing a sense of inevitability of climate catastrophe might leave one with the idea that there is nothing to fight for. On the contrary, progress has been made, and there is much, much more that can be done. The best antidote to climate anxiety is climate action. We must get active in our own rescue. So, if you are suffering from climate angst, but not yet working on it, check out some of the switch-to-climate resources above or drop me a note.

Climate anxiety isn’t accretive to your well-being. If you’ll permit a lapse into the philosophical, what is this life for? How do we choose to use this one precious existence that we have, against astronomical odds, been granted? I - like most or everyone reading this - am deeply privileged to be born into circumstances where I don’t deal with existential hardship in my daily life, but, ironically, it seems to be my privileged peer group that suffers the most acute climate anxiety. The world is complicated. And, yes, there is suffering out there, as there always has been, and there will be suffering also in the future. But there is also joy and beauty and love and meaning. These too will persist. So, whilst it is appropriate to sometimes connect with the grief of environmental damage, we shouldn’t allow it to crowd out our gratitude for being alive and being able to experience the world in all its richness. To do so would be to squander this life, the only one we get.

So what is the time frame for when you are trying to hit Net Zero? This is the question that is so often neglected.

Is it 2050, like most climate activists say is essential to save the planet?

Or is it 2150 (or something like that)?

The answer to the question drives policy options.

If your answer is 2050, then I am extremely skeptical whether technological innovation (or anything short of the collapse of the world economy) can achieve the goal.

If the answer is 2150 (or something like that), then I would say that technological innovation makes success very likely, but it requires little if any government policy beyond funding R&D for new energy sources.

So which do you choose?

The problem is that the current trajectory is unsustainable. Governments will run out of other peoples money. What happens when the spigot turns from todays fire hose to tomorrow’s annoying drip drip of the kitchen faucet? None of the businesses you mentioned are able to function on said drip. The key is indeed the pace and Michael above is dead right, the 2150-ish date matches much better with the finite nature of the FF energy system and prices will naturally be aligned with the new lower price of low CO2 energy solutions. The fact that your focus is in electricity generation and not the myriad other uses is a warning that you are still overly optimistic. Why not let the market take care of this?