- But the [Russian] lord, surveying vantage, with furbished arms and new supplies of men began a fresh assault.

- Dismayed this not our captains, [Zelenskyy and Klitschko]?

- Yes, as sparrows eagles, or the hare the lion!

Trying something a little different this week, given the week that is in it. I’ll avoid sharing any prognostications on the geopolitical / military situation, not those of others or, least of all, my own. But I’ll just share a couple of observations with regards to the intersection of the Ukrainian invasion and energy / climate action.

The events in Ukraine have marked a decisive turning point in history. People who have been watching this more closely will note that history has been running in this track at least since Crimea in 2014, but even before, since 2008 when NATO left the door open to Ukraine and Georgia for membership. But the invasion is a clear demarcation.

Russia has been able to build up significant foreign currency reserves (about half of which are now inaccessible due to sanctions) by supplying gas and, to a lesser extent, oil to Europe. The EU is Russia’s biggest export market, almost x3 bigger than the next biggest market (China).

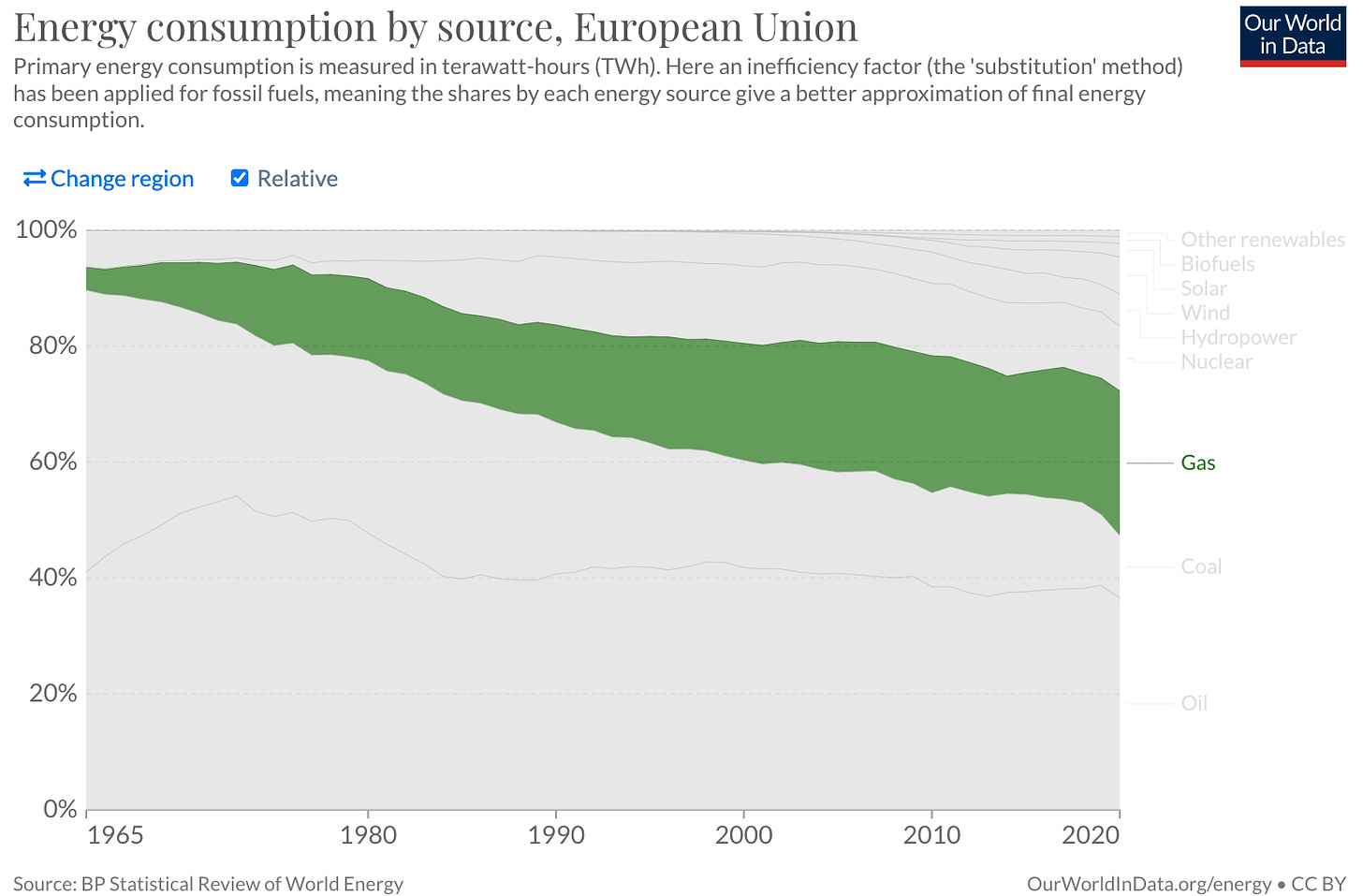

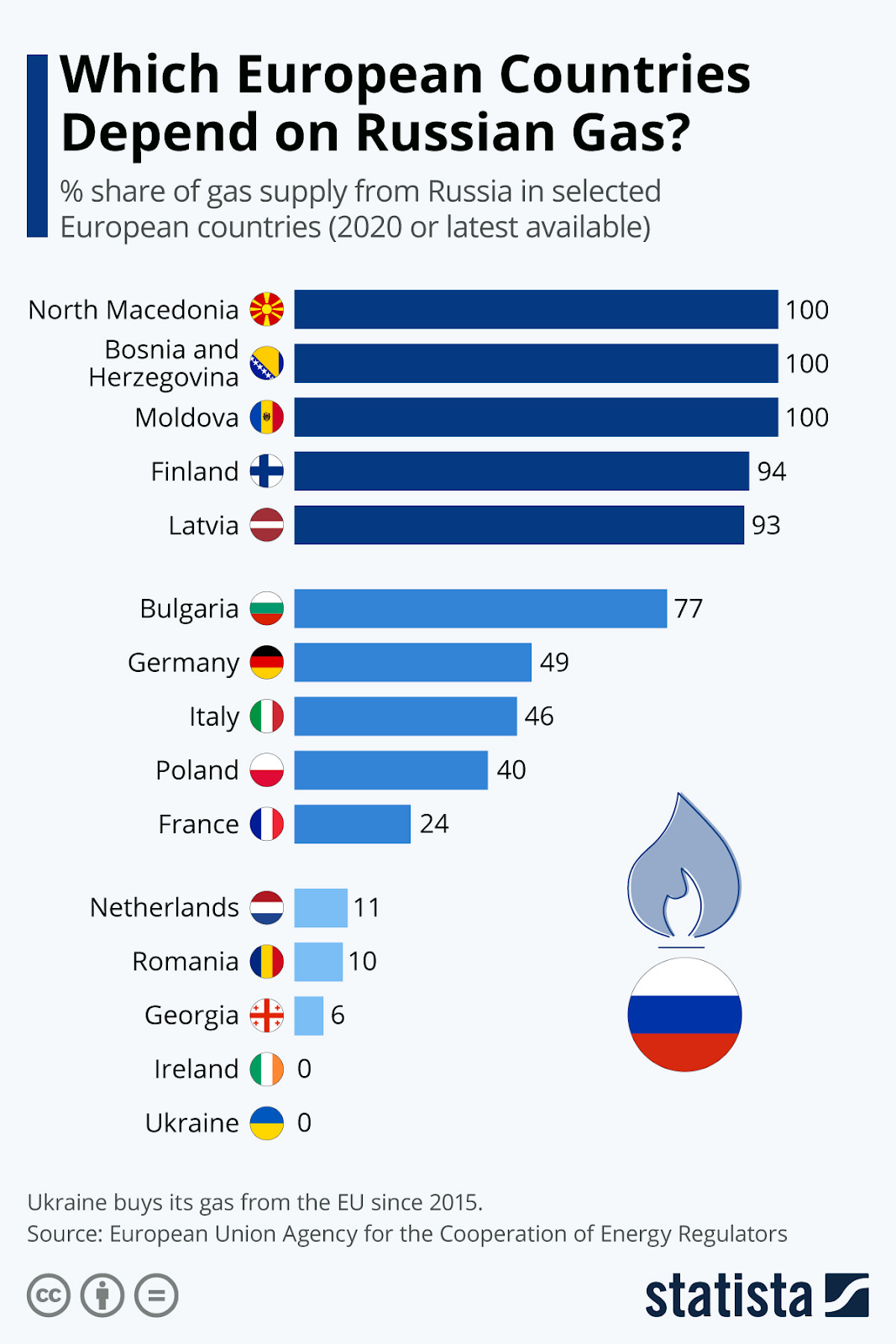

In total, Europe imports about 40% of its gas from Russia and gas represents 25% of the EU’s energy mix, a percentage which has been growing over time as coal is getting phased out. So in total Russian gas is about 10% of EU’s energy.

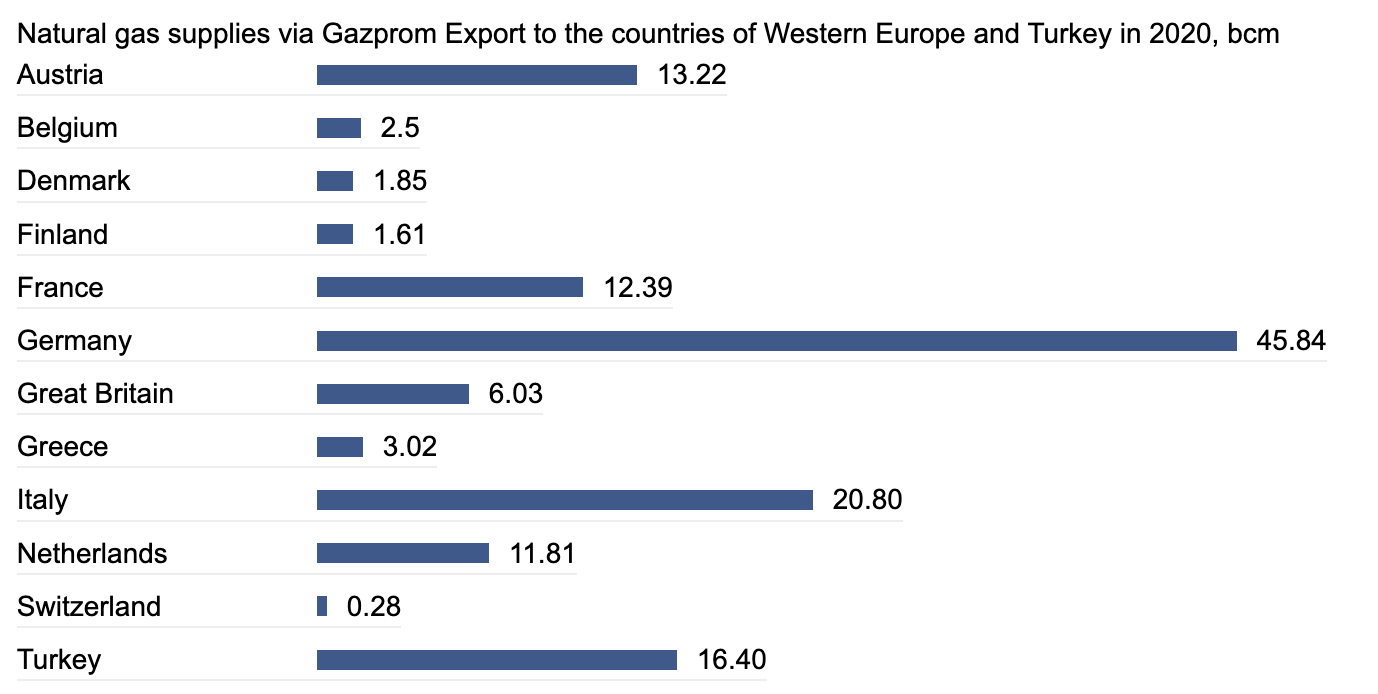

The dependency on Russian gas varies wildly between countries. Much of the press has been around supply to Germany. And Germany is indeed the biggest importer of Russian gas in absolute terms:

Source: Gazprom

However, there are plenty of other countries that lean on Russian gas. It is a bit complicated to cross reference the % gas imports from Russia vs % gas in the energy mix, but just to take a couple of examples - gas represents 42% of Italy’s energy mix, but only 7% of Finland’s energy mix. You can play around with the other countries’ energy mixes here (also, can be reminded how formidable the lift is going to be on renewables build out).

The implications for the energy transitions are complex, but, on balance, I would say positive. The order of priorities has shifted around. Decarbonisation is front and centre when security and affordability of supply are taken as a given. When they are not, as is now the case, meeting the energy needs of the economy becomes the priority and that will be done, by hook or by crook.

This gives us in Europe a dose of reality. It is easy to be dismayed at, say, China’s ramp up in coal use over the last couple of decades, but nobody in Europe, yours truly included, would be willing to swap our living standards for that of the average Chinese citizen a few decades ago, or even now. And, so, if it requires burning more coal, or wood, or anything else, to keep the lights on and homes warm, that is what Europe will do. We have a lot of levers. The IEA has published a 10-point plan to reduce dependency on Russian gas by between a third and half over the next year which include switching gas supply, extending lifetime of nuclear plants, steamlined permitting for extra renewables and accelerated deployment of heat pumps. The craziest stat in that is that reducing indoor temperature by 1 degree in winter would save Europe 10 bcm (billion cubic metres) of gas - a fact I’ll be leveraging in my own domestic thermostat battle!

So that is in the very short term. However, this is also a reality check on the implications of being in hock to resource-rich authoritarians. People in the climate community have been urging governments and corporates everywhere to treat climate change as the emergency that it is and to mobilise as if it is a war effort. Now, it literally is. Climate action and national security have always been linked, but this crisis has made it impossible to ignore. And, indeed, governments seem to be on it. In a big step, Germany has moved forward its 100% zero carbon electricity target to 2035, which will see offshore wind and solar quadruple in the next 10 years and onshore wind double.

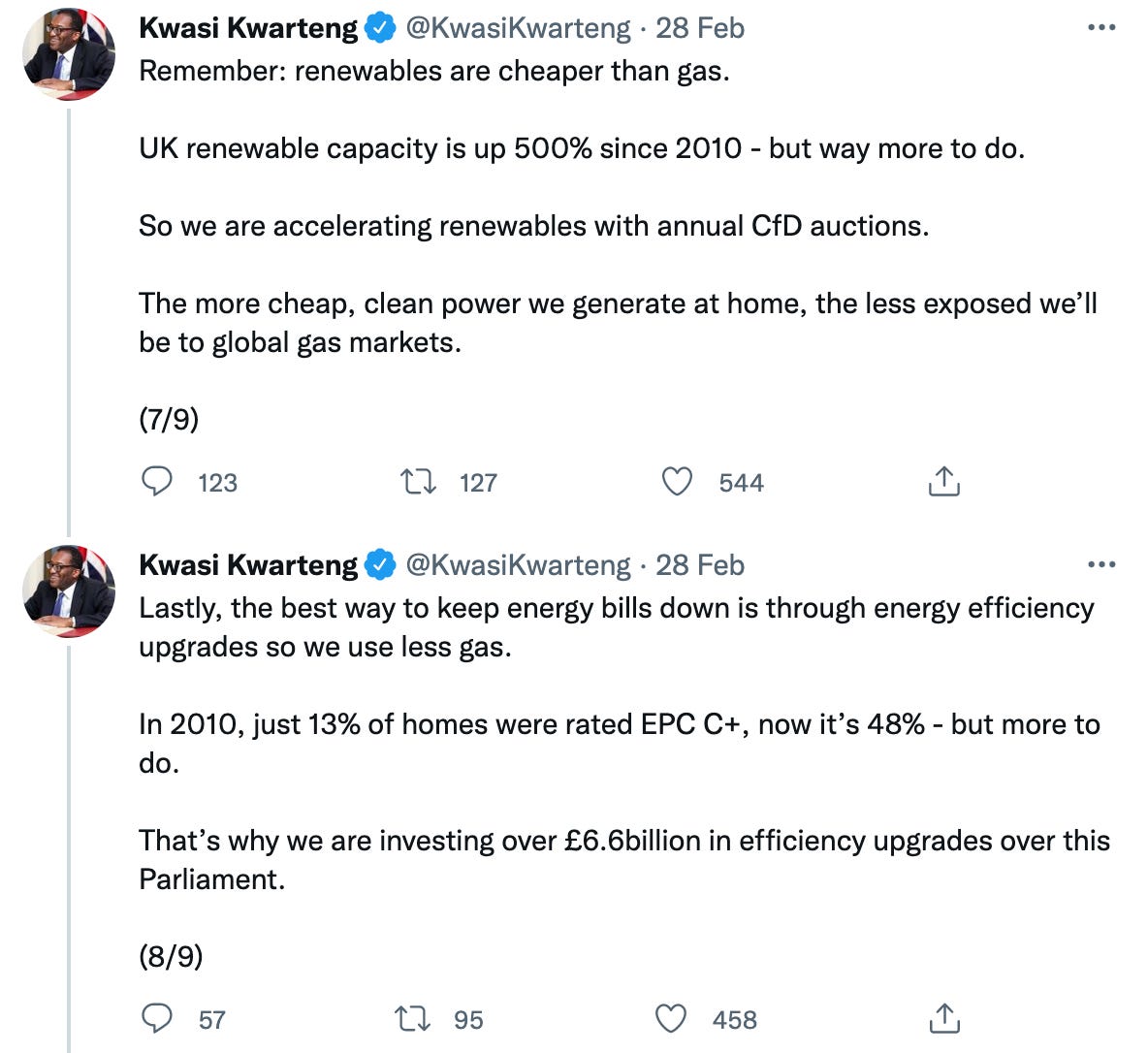

Energy security is less of an issue for countries that don’t lean on Russian supplies, such as here in Ireland, but they are still subject to global market prices, so affordability becomes a key consideration. UK Secretary for Business & Energy Kwasi Kwarteng laid out the UK priorities in this Twitter thread - maintain North Sea supply, more nuclear, more renewables, more efficiency.

The high gas prices for the foreseeable future increase returns on investment and decrease payback periods for all efficiency measures and make the costs of renewables even more favourable in relative terms. This, coupled with emergency mobilisation, improvements of permitting, etc from government, should see a significant acceleration of

This is a dark hour in our history. I didn’t really think I’d live to see a moment like Poland ‘39. Beyond the immediate crisis and the plight of the Ukrainian people, it increases the variance of outcomes for the world order going forward and the possibility of tackling large coordination challenges (like climate).

However, Putin has provided a rare - increasingly rare - cause for unity across the West and a strengthening of resolve NATO, and, you’d have to say, has generally snapped us out of the delusion that we’d escaped the big gyrations of history. Putin may have been trying to bolster his internal position by focussing on external so-called enemies, but has in the process united the world against Russian aggression. Addressing the unfolding humanitarian crisis and meeting our energy needs by any means are now the immediate priorities, but the necessity of having secure and affordable (and hence, for most, low-carbon) energy supply have been crystallised like never before.

For the second time in as many years, the world has been galvanised to action - “build back better” is now a war-time imperative. Action is the antidote to despair, as we are being shown now by the brave Ukrainian people. Action will be required of all of us in the months and years ahead.