The recently released IEA report is mostly encouraging and documents a sufficient number of remarkable numbers that I thought it would be worth highlighting some of them here. A few of my takeaways:

Deployment S-Curves: Longer and steeper than almost everyone thinks. Renewable capacity additions grew by 50% (!!) in 2023 to 507GW, the fastest growth rate in the past two decades. The IEA revised up its forecasts by 33% from last year (a new record), having revised them up last year by 30% on the previous year (itself a record upward revision at the time). I’d wager the COP28 ambition to triple renewables capacity by 2030 will be comfortably met (the IEA sees them only hitting 2.5x).

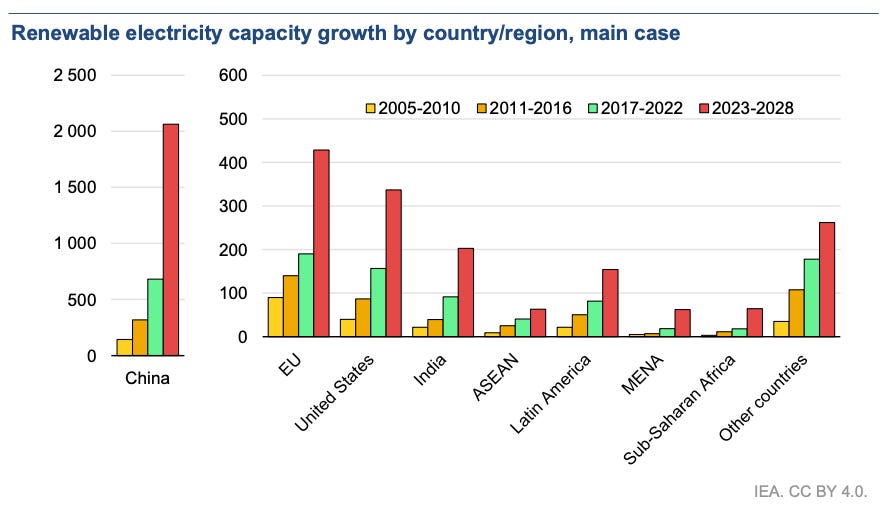

China: Whilst isn’t the whole story, it is almost the whole story, both in terms of domestic deployment and supply chain dominance. Nearly the entire upward revision to the global forecast was driven by an upgrade in the China forecast. Whilst the West may want to support some domestic players for strategic reasons, global energy transition isn’t possible without China.

Supply growth vs demand growth: At the risk of stating the obvious, to decarbonise we must shut down existing fossil infrastructure, not just build more renewables. Or, to put it another way, we need fossil generation to be reduced in absolute terms, not just relative terms. The incredible growth of renewables has allowed emissions in the power sector globally to level off (coming down in developed markets, growing more slowly in developing countries), but to see it actively bringing emissions down, it needs to start edging out coal in China and India, where electricity demand growth is robust. The report doesn’t get into this important area.

Permitting and transmission: These stand out as the two biggest drags on growth pretty much across markets.

Heat: Accounting for almost 40% of energy related emissions, we are still way behind on decarbonising heat, with low-carbon sources accounting for just 13% of the total.

China:

China installed more solar in 2023 than the entire world did in 2022, slightly more than doubling its pace of deployment. Wind capacity additions also grew by a whopping 66%.

China is expected to account for almost 60% of all new renewable capacity between now and 2028. It is expected to deploy 4x the amount of the EU, 5x the amount of the US and 10x the amount of India.

China is expected to reach its 2030 target for wind and solar installations this year, in 2024, six years ahead of schedule.

Despite aggressive expansion of solar manufacturing capacity elsewhere driven by government incentives, China is still expected to maintain market share (80-95%, depending on the part of the solar value chain).

Costs:

Prices for solar modules dropped almost 50% (!!) year on year amid huge growth in manufacturing capacity, now triple what it was in 2021. [The trajectory of module cost declines drove the key insight of Erthos that efficiency didn’t need to be maximised, and could take out the costs of steel and some soft costs by laying them directly on the ground.]

Almost all (96%) of new utility-scale wind and solar had lower generation costs than new gas or coal plants, with 75% being cheaper than existing fossil generation.

Although the IEA notes that the generation is expected to continue to get cheaper for wind and solar, it doesn’t expect much of a change in competitiveness due to higher integration costs for variable renewables.

Renewable electricity forecasts:

It’s worth noting right out that the IEA’s forecasts should be taken with a pinch of salt. Or, more specifically, they reliably have to upgrade their forecasts year after year, so the below are almost certainly too conservative and should be treated more as a floor than a base-case:

Renewable capacity additions of 3700GW in the main case over the next 5 years.

Wind and solar to represent 25% of electricity production by 2028, with all renewables (including hydro) representing 42%.

Wind and solar to bypass nuclear generation in 2025 and 2026 respectively (nuclear is currently second to hydro in terms of low-carbon electricity production)

As noted above, this is very much driven by China, which is expected to triple its rate of additions over the next 5 years vs the last five years. Almost all of the IEA’s massive upward revision to last year’s forecast is due to upward revision of China (+64% vs previous).

Offshore wind is going backwards, due to well flagged challenges around inflation, supply chains, interest rates, and long lead times.

Key bottlenecks:

Inflation / higher interest rates, modifying auction structures etc. - requires policy response, changes to auction processes, etc.

Grid infrastructure, new transmission and long interconnection queues

Permitting - takes too long, 1-5 years for utility solar and 2-8 years for wind. [Increasing objections to wind farms will likely limit its growth vs solar.]

Financing in EM - increased country risks from policy uncertainty and weak local utilities means projects aren’t affordable with risk-adjusted returns - needs some concessionary finance.

Sunk costs in Asia: The report notes a huge overhang of fossil (mostly coal) capacity in major Asian countries - Indonesia, Philippines, Malaysia - where excess capacity is north of 50% and, in Indonesia’s case, 90%. Utilities have been locked into take or pay contracts with the coal generation assets, which makes it prohibitive to contract for new renewable generation. [This is one of the things that the Just Energy Transition Partnership for Indonesia is supposed to address.]

Heat:

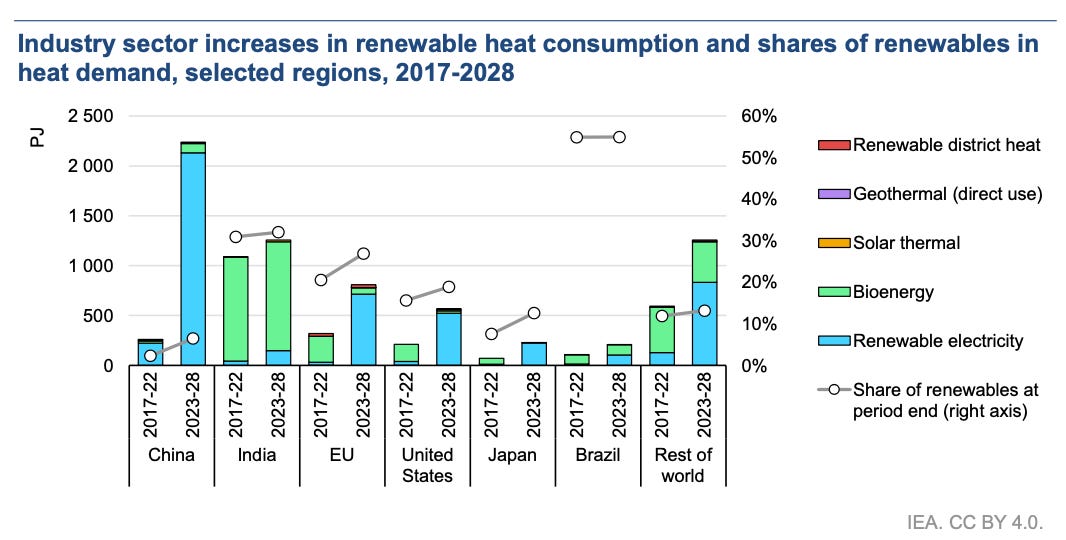

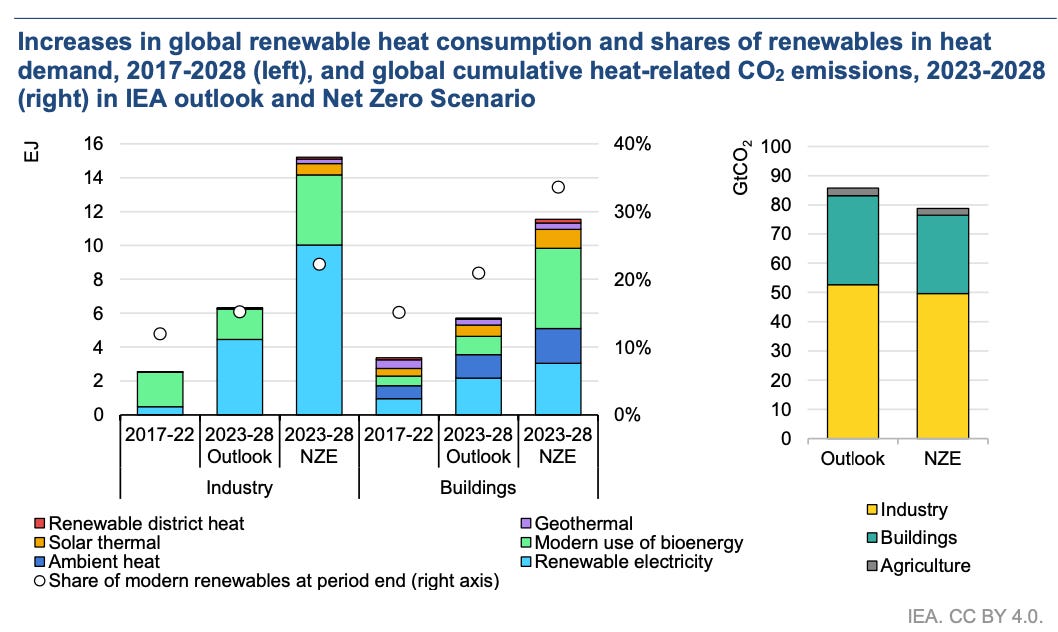

Heat accounts for 38% of energy-related CO2 emissions and they are growing. Over the last 5 years, head demand increased by 6% with only half of the growth covered by expansion of low-carbon sources. Furthermore, even with growth accelerating (the IEA revised up its forecast by 17%), it is not expected to keep pace with growth in heat demand, so emissions are expected to continue to rise.

If fossil fuel use is not contained, the heat sector alone in 2023-2028 could consume more than one-fifth of the remaining carbon budget for an even chance to limit global warming to 1.5°C

Growth in demand: All of the anticipated demand growth for heat in the next five years is expected to come from the industrial sector, with building heat demand staying flat (increases in some regions through increased activity or living standards being offset by efficiency improvements elsewhere).

Most of the expansion of renewable heat in industry will come from renewable electricity (India being the big exception), but the relative percentage of will remain relatively low, especially in China, where it counts. [A potential upside scenario is that, given that China is outpacing all the forecasts for renewable electricity, they might have sufficient abundance of low-carbon electrons to electrify industrial heat faster than expected.]

Buildings: The IEA sees a sharp drop (-17%) in the use of traditional biomass (wood, charcoal) driven by urbanisation trends and policy in China and India. [Clean cooking in sub-Saharan Africa remains a massive challenge / opportunity.]

Heat pumps: The IEA notes the Europe saw a record 39% increase in heat pump sales in 2023 and the US saw heat pump sales eclipse gas furnace sales for the first time. There have been nearly EUR 5bn of heat pump manufacturing announcements in Europe for the next three years.

In order to be on track for Net Zero goals, there needs to be a massive acceleration of the deployment of renewable heat, mostly through electrification of industrial heat, but also, and somewhat surprisingly, through increased use of bioenergy for heat in buildings.

Biofuels:

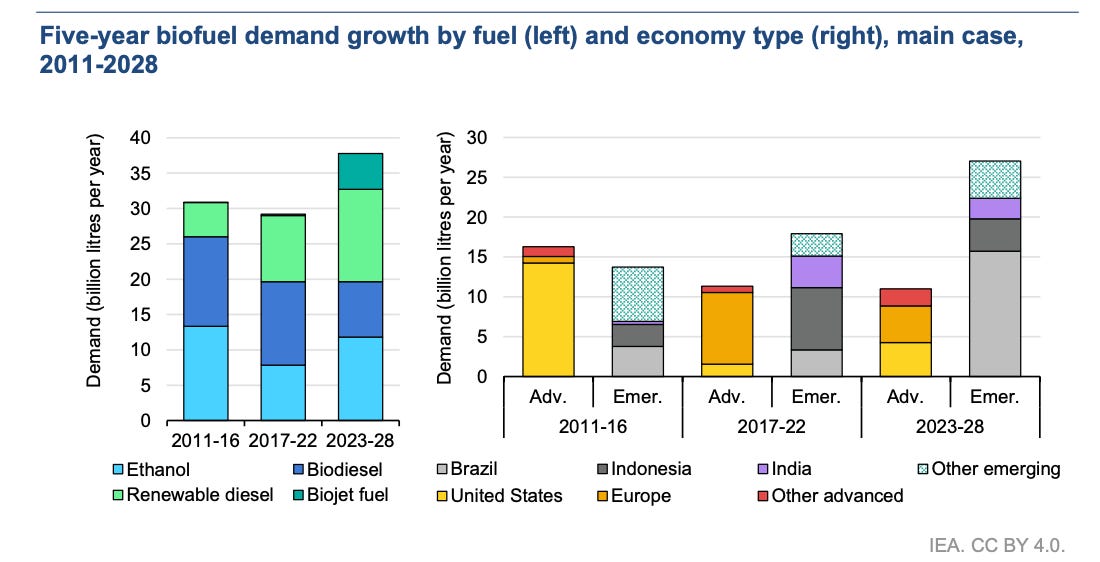

There hasn’t been any notable acceleration of growth in biofuels over the past 5 years, with the IEA only expecting modest increase in the growth rate over the next 5 years, driven by Brazil, which is massively expanding ethanol production.

Part of this is a good story, because electrification of transport is expected to dampen demand for liquid fuels in developed markets. From the IEA: Biofuels and renewable electricity are set to reduce transport sector oil demand by near 4 mboe/d by 2028, more than 7% of forecast transport oil demand… Historically, biofuels have reduced oil demand the most, but during the forecast period, electric vehicles claim a larger share of reductions in the gasoline segment.

Biojet: Even in the accelerated case, biojet would only eke up from 1% to 3.5% of jet fuel by 2028. We are a long, long way from having the supply of low-carbon liquid fuels we need to decarbonise aviation. [Incidentally, we have seen increasing interests from VCs in investing in technologies that scale bioenergy as the challenges of efuel inefficiencies become more apparent.]

These are all very interesting statistics, but I think a key point is missed.

It is important to note that from a climate perspective, increased solar and wind is not supposed to be a goal in and of itself. It is supposed to be replacing fossil fuels, especially coal which produces the most carbon dioxide emissions per unit of energy (other than wood).

There is very little evidence that this is actually happening. Increased solar and wind is in addition to coal, not instead of coal.

If you doubt me, follow up on my challenge:

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/prove-that-solarwind-replaces-fossil

Great review of the state of play!

I was interested to see your note regarding bioenergy – "we have seen increasing interests from VCs in investing in technologies that scale bioenergy as the challenges of efuel inefficiencies become more apparent". My understanding had been that biofuels from dedicated biomass (crops planted specifically for use as biomass) is basically a horrible idea under all circumstances, due to large use of land, water, and fertilizer, not to mention all of the downstream processing that then needs to be done. (I wrote about this a while back at https://climateer.substack.com/p/biomass-overview.) Is the interest you're seeing around other forms of bioenergy, such as fuels from waste biomass? Or are sensible use cases for dedicated biomass emerging?

Conversely, I'd been holding out hope for efuels, especially as the price of solar power as an input continues to fall, but I haven't been following progress there.