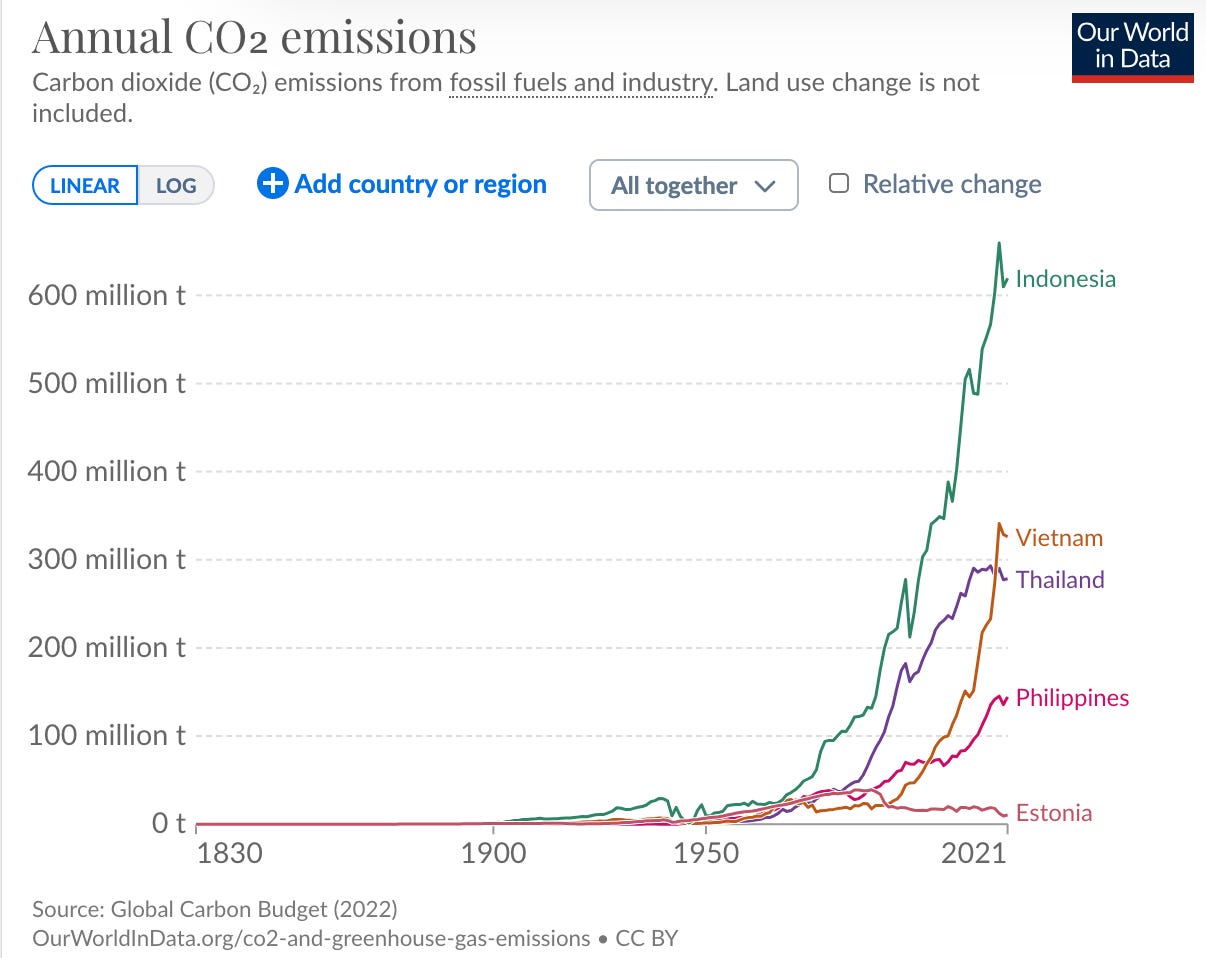

Today I get to combine two of my favourite things - large-yet-neglected pieces of the climate transition, and (mostly) positive news! We talk a lot about focussing on the big pieces of the decarbonisation pie. In general, this is in the context of sectoral focus (e.g. clean cooking access or industrial heat vs, I dunno, sustainable yoga mats), but it is also true for geographical focus. It is a source of constant frustration to me the dearth of readily available information on China in particular, but Asia more generally. China is hands down the most important global actor in the energy transition, both because it is the biggest emitter, but also the critical piece in the clean energy supply chain and is spanking the rest of the world in terms of deployment. (I’ve written a bit more about their climate action approach here and here, for anyone who wants a quick orientation.) I was very pleased to unearth a podcast miniseries from Assaad Razzouk, shining a light on the substantial environmental progress across some of the major population centres and economies of SE Asia - China, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Philippines. Outrageously, he found that Western media coverage of climate action in Estonia (emissions 10 million tonnes CO2e) was greater than that of Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand combined (combined emissions 1350 million tonnes CO2e). I think it’s worth including the chart to make the lunacy of this parochialism even more apparent:

Luckily, these countries have been quietly making some steady progress on the environmental agenda. I’ll return to China, but, since I’ve covered it to some extent before, I’m going to begin with Indonesia.

First some context.

Indonesia is the world’s fourth most populous country with a population of 280mm, putting it just after the US and ahead of Pakistan.

It is the largest economy in SE and expected to become the 7th largest economy in the world by 2030.

The country is made up of 17,000 (!) islands.

Third largest rainforest nation after Brazil and DRC.

Not where it needs to be: To be clear, Indonesia is quite a ways off from where it needs to be on climate action. The good news covered here is primarily on the direction of travel across a number of environmental issues.

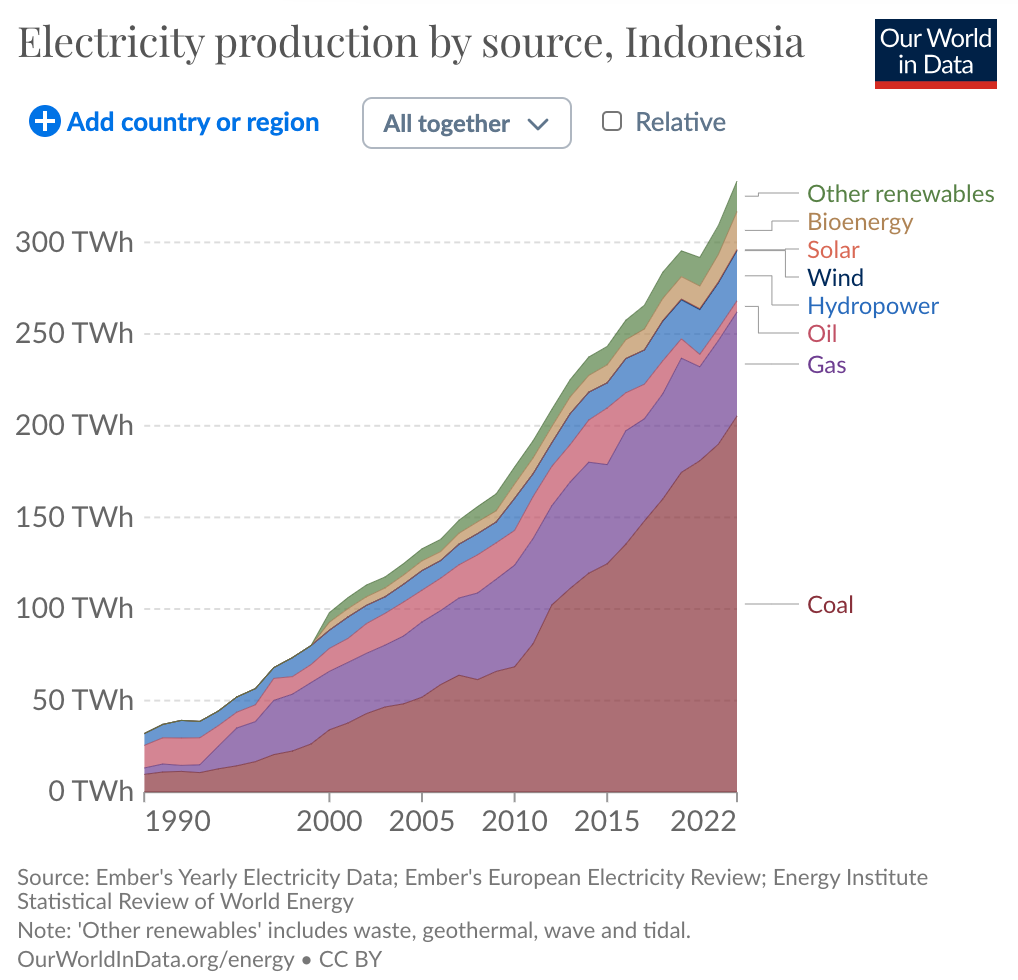

Electricity mix - the bad news: Indonesia has a deep dependency on coal, of which it has domestic supplies in abundance. Their progress on installing wind and solar capacity is so close to zero as to be indistinguishable (and, on the below chart, invisible).

JETP: If we might have some cautious optimism that there is a path for early coal plant retirement, it will come via the Just Energy Transition Partnership that was announced with much fanfare last year, that would see wealthy countries invest $20bn in helping Indonesia to reach peak emissions in the power sector by 2030. The initial investment plans from the country were expected this summer but have been pushed back to the end of the year to allow technical teams more time to prepare recommendations. Those should be hotly anticipated. For an insight into how they might look, Carbon Brief has a post on it (TL;DR - the $20bn should be used to buy out coal PPAs and make way for solar generation capacity, which will make up most of the electricity in a decarbonised grid). If there is some short-term boost to renewable energy, it might come by way of demand from Singapore, although that deal is far from done.

Clean energy manufacturing: Whilst there has historically been a lack of ambition for domestic clean energy, Indonesia is trying to make itself a rival, or at least alternative, clean energy manufacturing hub to China. It has famously restricted the export of nickel (a key ingredient lithium-ion battery cathodes) as a raw commodity, instead forcing international firms to set up processing and manufacturing facilities on-shore, including from CATL and Tesla. Ironically though, Indonesia’s Green Industrial Park is going to be powered with coal until some of the proposed hydropower projects can get permission and come online.

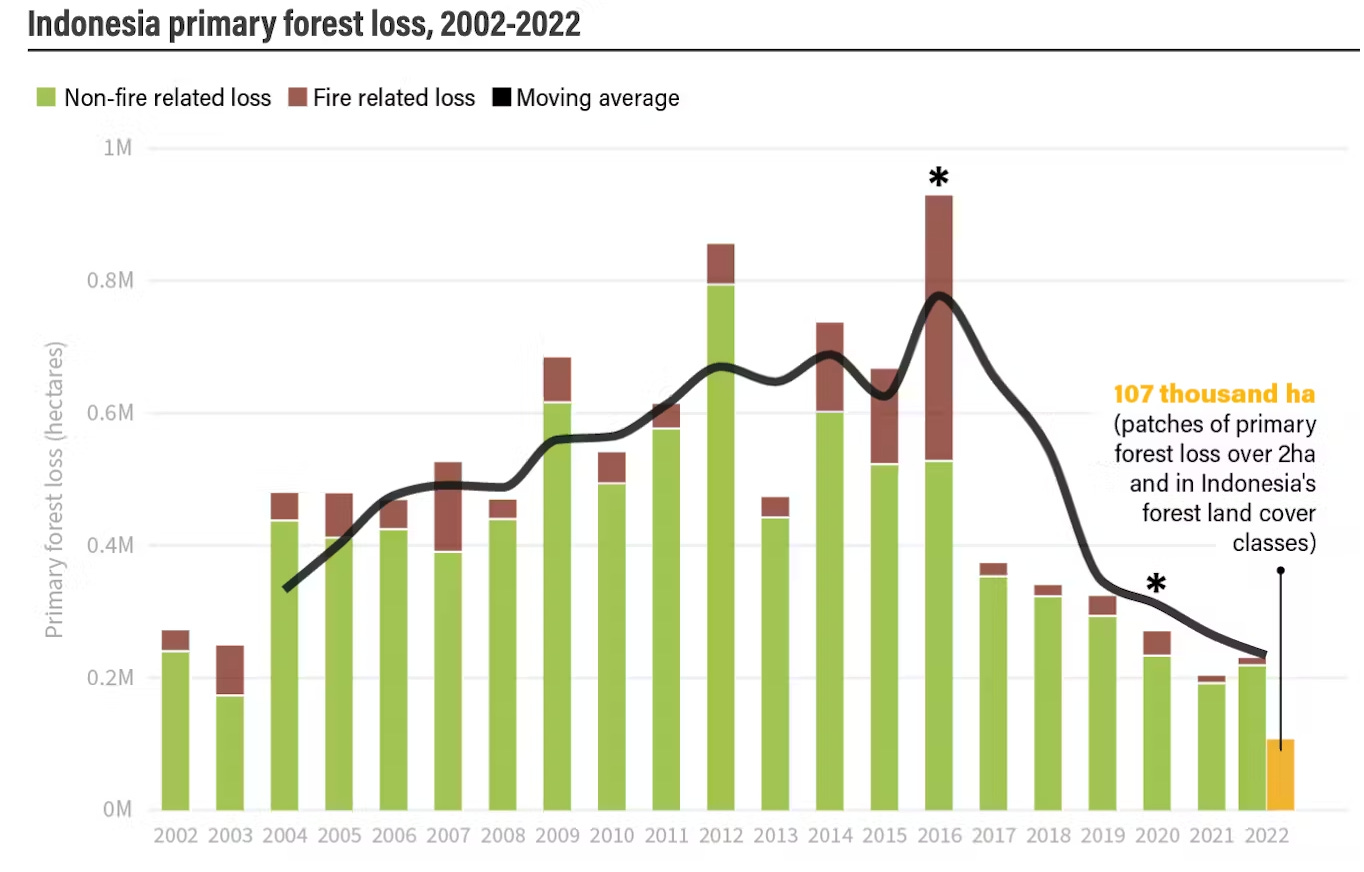

Deforestation: Going back 10 years, Indonesia was deforesting their rainforest faster than any other country to make room for (mostly) palm oil plantations. But over the last number of years, deforestation has fallen precipitously.

The government placed a moratorium on clearance of primary forest and peatland in 2011. However, this has taken quite a bit of time to start taking effect, and has been plagued with difficulties on implementation and enforcement, given Indonesia’s highly distributed geography across the islands, as well as some in-built loopholes. One study suggested that it contributed little-to-nothing to reducing deforestation up to 2018. The marked improvement in recent years though is in part due to better enforcement and stricter permitting (although, alongside this, it may include transient factors like wetter weather from La Niña and lower palm oil prices). The good news is that civil society are actively working on consolidating and extending these protections.

Deforestation pressure will continue to improve as regulation tightens on companies to root out deforestation in their supply chains. Most notably, the EU this summer passed the EU regulation on deforestation-free supply chains, which prohibits the manufacture or export of anything that is produced with commodities linked to deforestation. Companies have until the end of the next year to ensure compliance. Indonesia is already encouraging companies to produce palm oil using sustainable practices and requiring special permits to expand production onto peat lands.

Protected areas: Indonesia has 150,000 km^2 of protected land area and almost 300,000 km^2 marine protected areas. The current administration has introduced 10 new protected areas across the country and it has a target of protecting 10% of its territorial waters by 2030 and 30% by 2045. Whilst Razzouk notes that local communities are enthusiastically taking responsibility for monitoring and enforcing these areas, reports from elsewhere indicate that the effectiveness of protection is severely undermined by a dearth of funding. However, the country did issue its first Blue Bond (about USD 130mm) earlier this year and in its comprehensive Blue Economy Roadmap, released this summer, also refers to the establishment of a national Blue Carbon Framework to preserve and grow its 3.3mm hectares of mangroves and 1.8mm hectares of seagrass.

Plastics: Indonesia has bans on plastic bags in certain areas, which is making a huge difference on single-use plastic. It has also been working on dealing with marine plastic waste, which includes publicity campaigns as well as clean up efforts and establish waste management infrastructure. They also introduced Extended Producer Responsibility, whereby the producers of plastic are made responsible for their ultimate collection and disposal. I also noted that Ocean Cleanup had their first river intercept in Jakarta, with a second one now under contract.

Bela, Indonesia is moving to use nuclear power. ThorCon is developing liquid fuel advanced reactors that generate electric power that is less expensive than from coal fired plants. See ThorConPower.com. See ThorConPower.com/news for the latest on regulator actions.